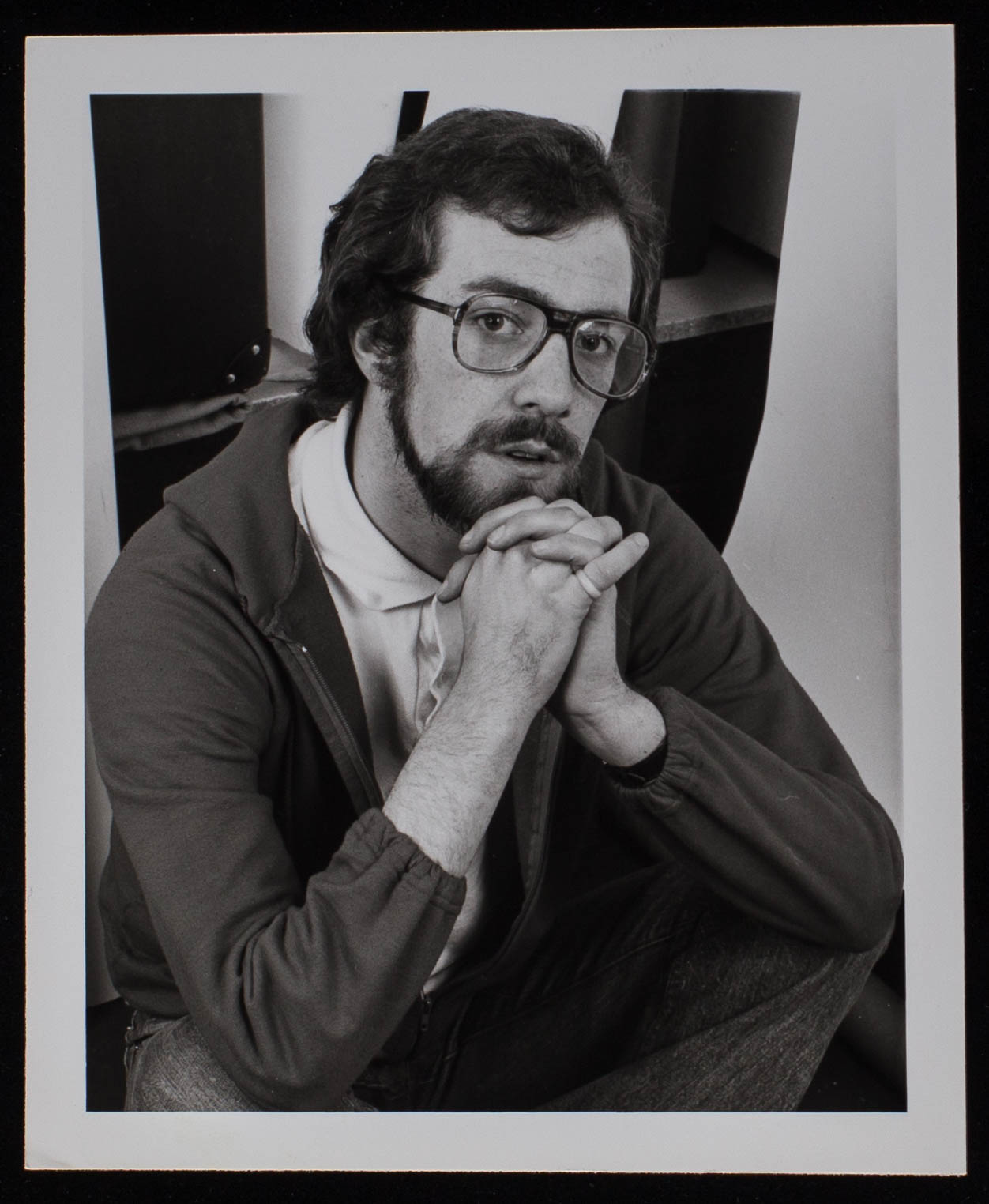

Roland Jeffery, General Secretary of London Friend from 1975 to 1977

Roland Jeffery was the General Secretary of London Friend from 1975 to 1977, and the charity’s first paid worker. After London Friend, he went on to work in Heritage regeneration. He currently is the volunteer coordinator at Isokon Gallery.

What made you apply for the role of General Secretary and motivated your work, at a time when gay people were ostracised and closeted at work?

I came to work for London Friend in September 1975, immediately after university. I was the organisation’s first paid employee and for some reason my post was oddly titled General Secretary. This made it sound like a large organisation and a trade union, so doubly misleading!

For me, it was a question of pursuing gay activism, which I had become involved with as a student, or taking a different direction and going for conventional career track job, as most of my fellow students were doing. I remember sitting in the park with the job offer from Friend in one hand and another for a graduate trainee scheme in the other, and thinking this feels like a fork in the road. I had come out aged 16 at school in Northern Ireland so a large part of my decision was: could I be openly gay at work or would there be hassle, or worse?

Tell us about your inspirational work and a standout moment as a general secretary at London Friend

Friend was a young organisation but already there were fifteen Friend groups across the country; it was an organisation whose moment had come and there was change in the air. All of the groups were entirely powered by volunteers, which was humbling. I was the sole full-time staff member and there was one part timer to help keep the office open daytimes.

The first task I had was moving London Friend’s operations from a temporary office in Westminster that was due to be demolished across to Islington; this was a condition of the grant we had been awarded. Having started out in a corner of a volunteer’s flat in Earls Court three years earlier it felt like a huge jump to an Upper Street, Islington address with a shopfront and three floors of rooms for admin and counselling. Of course, Upper Street was not as smart in 1975 as it is now and the rent on our premises was quite reasonable and the premises had been sitting empty for three years before we took the lease.

We also had to get incorporated as a charity; now we had a little money we had to account for it! The grant was 75% from the Home Office and 25% from Islington. It is easy to forget how even liberal and progressive politicians then saw sexuality as a totally private (and largely shameful) issue, not as a political one or a matter of human rights.

Incredibly this political double-think continued until the early 1980s, in spite of the Jeremy Thorpe affair, and several other scandals. But Islington councillors had the guts to sponsor London Friend’s grant application and Roy Jenkins signed it off as Home Secretary. The fact it went so high in the Home Office in spite of being a minute amount in terms of the Home office budget showed how unusual it was. We were the first gay-led organisation of any kind to get a public grant and that fact alone attracted quite a lot of press attention.

What kind of developments took place for London Friend in this period and how did the current political context influence them?

At that time (1972-75) we branded ourselves as a ‘befriending and counselling’ organisation and a good deal of support we gave was on the phone, rather than face-to-face.

We saw a lot of our work as befriending—today it would be called peer group support—rather than counselling. But alongside telephone befriending we did host several groups in our new premises, including two which had a closed but rotating membership and were led by professionals. Other groups were social discussion groups intended to give those attending the confidence to meet socially outside Friend.

For the great majority of service users we were the first contact people had with openly gay lesbians and gay men. Taking on the Upper St premises meant we could see lesbians and gay men privately as well for more in depth one-to-one discussions. A number of members of the Gay Social Workers and Probation Officers Group joined and helped to build that side; but they came to London Friend as lesbian and gay volunteers first, even though their professional training and counselling skills were greatly valued.

The grant meant we could place paid advertisements in the press. They were only tiny ads in the classified columns, but the response was astonishing. If there was one in the Sun or Daily Mirror, all four phone lines would be ringing off the hook for days after. There was a huge pent-up demand for what we offered. The Daily Telegraph and The Times refused our ads, the latter on the personal decision of the editor, William Rees-Mogg, who also insisted that a news story about Friend put the word ‘gay’ in quotes throughout.

We introduced a more formal interview and selection process for volunteers and it was always axiomatic that they identify as lesbian or gay and were prepared to do so to clients; of course there were volunteers who had been in different-sex relationships, who had children or who identified as bisexual; but it was important that our callers and visitors spoke to us as people living a life as non-heterosexual people. We didn’t expect callers and service users to come out unless they were ready to do so; but we did expect our volunteers to be open about their sexuality. Quite a bit of our befriending was talking people who wanted to come out through the process, especially if they were in jobs where it was not then acceptable to be known to be gay. I still vividly recall conversations I had with a coal-miner, a bus driver and a barrister who faced that situation; I sometimes wonder how things worked out for them in the longer term……

We celebrated Friend’s fifth birthday in our offices with a big party that was filmed by the BBC for broadcast. Maureen Colquhoun MP was supposed to be our guest of honour and her appearance would have amounted to her coming out. Journalists started ringing the office, scenting a hot story, but Maureen’s constituency Labour party threatened to de-select her if she attended and Graham Chapman from Monty Python stood in at short notice. Sadly, Maureen was de-selected as MP anyway, in no small part because she became open about her sexuality.

Roland Jeffery. Photography by Bob Workman. Credit: Hall-Carpenter Archives, London School of Economics

How was London Friend different from the other gay-led organisations?

We had generally friendly relations with a wide range of other organisations, both those that were led by lesbians and gay men; and mainstream ones too, provided they demonstrated the kind of acceptance of alternative sexualities we expect before we would refer service-users to them. There were one or two professional social work and counselling bodies who declined to engage with us — though I understand they have overcome their institutional homophobia since. Several mainstream ‘agony aunts’ in the national press and on radio gave us fantastic free publicity as an organisation and championed a more enlightened view of human sexuality.

One forgets in this age of self-help and the internet how difficult it then was for anyone to access frank and realistic advice on sexuality and sexual issues. It took the massive, unmissable tragedy of AIDS in the following decade, to break down many barriers like that and force issues of sexuality into public discussion.

What was your experience with London Friend and the people who worked there as volunteers, service users and supporters?

The volunteers at Friend in the short period I worked there were awesome. Many gave so much to the organisation and its service users. It could be really emotionally draining at times, but there was a supportive and energetic team spirit. Most volunteers had jobs and household responsibilities too. There were between 50 and 60 volunteers in London Friend at that time and many gave way beyond the hours that the committee flagged as a minimum commitment. In terms of value for money our small government grant unlocked a huge stock of energy, skill and commitment.

What is the change you’d love to see in our community?

Occasionally I pinch myself that I have been lucky enough to live through the transformational changes since the 1970s. Many of us fought and took risks for change, but there were some set-backs and real moments of doubt: progress is never inevitable. I’d like to see the same kind of progress in those countries and regions where homophobia is still the norm. We need to support those fighting for change in those parts of the world—some of which are in Europe!

Thanks to National Lottery players